Apocalyptic and Apocryphal Tradition in Matthew 14

Introduction: Images of Jesus and Their Composition

Following the Feeding of the 5,000, last week’s Sunday Post, in this week’s assigned gospel reading from the Revised Common Lectionary, Matthew 14.22-33, Jesus walks on water, helps Peter to do the same, guards against disbelief, and calms a turbulent sea. I’m not including the passage here, so do go and follow that link to Matthew 14 to familiarize yourself with the details.

I acknowledge the risk of this project—this newsletter, I mean—to reduce the reading to its component literary allusions at the expense of a forest-for-the-trees meaning-making endeavor to interpret the story and not just expose the scriptural infrastructure on which it hangs.

I’m reminded of my kids assembling a 250 piece puzzle on our dining table: locate the frame pieces, cornered or flat on one side, divvy up who’s working on which major element in the composition, jockey for who places the final piece in the puzzle, and marvel at the finished product. Then comes dinner and the instruction to clean up the puzzle and set the table for the meal. This instruction is always met with resistance. The whole seems more valuable than the pieces and process that compose it.

This is the risk of the interpretive project. What does it matter why an ancient author writes that Jesus walked on water, isn’t the point of the story to ask why did Jesus walk on water or even that he could? That the author may be mindful of this or that tradition when composing the text—fallible conclusions at best—is an intellectual exercise, when the real value of reading these stories, you may think, is to reveal the nature of Jesus, the one they called the Christ, and what this revealed nature means for Christ followers, then and today.

Two reasonable responses come to mind, one general and a second more particular: First, two things can be true at once, we can respect the composition of the text while also respecting that many people (2.5 billion worldwide) follow Jesus as the anointed one, the messiah, commissioned by God to offer redemption for sins, “raise the saints who have fallen asleep,” like Matthew says, and invite all of God’s people into the kin-dom of heaven, and can adhere to these things irrespective of biblical criticism. These are not mutually exclusive commitments.

Plenty of scholars of religion, like Professor Aaron Higashi, who I’m a big fan of, speaks often about reconciling his scholarship and personal faith, like in this Instagram reel:

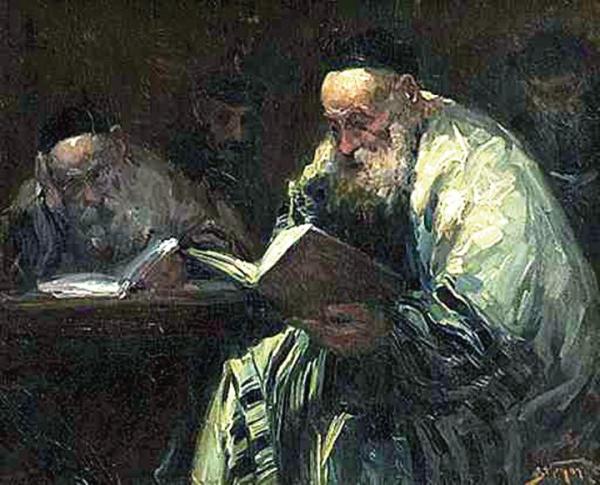

Second, it is useful to distinguish the attitude toward the sacred texts held by Christians and that held by Jewish people. We’ve noted in this newsletter that roughly defined, Christianity is about something to believe; whereas, Judaism is about a law to follow. I don’t want to be too rigid in the way I define these boundaries—certainly they are porous, as evidenced by the plurality of Jewish-Christian, pagan-Christian, and Jewish non-Christian beliefs in the first three centuries of the common era.

Moreover, many Christians would slough off the Christian label and adopt the moniker “follower of Jesus,” which suggests following, a commitment to emulating behavior and upholding moral conduct, as I’ve suggested is integral to the first century Jesus movement. In fact, Paula Fredriksen, in her book, From Jesus to Christ, argues that Jesus’ intensification of the law (Torah) was indicative of end-times cults in the first century. And so, there is plenty of overlap, but I think the general assessment holds.

For Christianity, credal and doctrinal commitments emerge from study of the text. Death and resurrection are central to the Christian project, and adopting the “right beliefs” with respect to Jesus’ death and resurrection is key to one’s own salvation. The centurion at the cross is suggested to be the first Roman convert to Christianity because of his witness of the crucifixion and proclamation that Jesus is Son of God; not circumcision and adherence to the law.

For Jews, an ethno-religious identifier is the boundary marker and observance to the law (Torah) is the practice. Again, careful not to be too rigid, but it’s illustrative to note that Jewish attitudes toward conversion, when non-Jews join Judaism, affirms that when converting, you are also at Mount Sinai—to do what?—to recieve the law!

This personal account shared on the Reform Judaism blog uplifts this tradition:

As someone whose Jewish journey included conversion, one of my favorite teachings is that Deuteronomy 29:13-14, “I make this covenant with its sanctions not with you alone, but both with those who are standing here with us this day before our God and those who are not here with us this day,” refers to those who were physically present at Sinai and the souls of future generations of Jews and those who decide to make their spiritual home among the Jewish people through conversion (Babylonian Talmud Shavuot 39a).

Significance of the Talmud and the Law

How does this play out in the different attitudes that these communities, Christianity and Judaism, respectively, hold toward the texts? For one, Jews have penned voluminous writing on proper law interpretation. Two Talmuds were penned, one in Jerusalem, the Talmud Yerushalmi, and the second in Babylonia, present-day Iraq, the Talmud Bavli—like you see cited in the block quote above, “Babylonian Talmud Shavuot 39a.” These Talmudic writings collect the debates and positions of Rabbis over 300 years interpreting the Torah and offering instructions for Jews. The Talmuds are the daily instruction manuals for Jews—how to interpret the written law (Torah), in daily practice. These include rules for prayer, rules for dress, rules for maintaining the dietary rules, rules for ritual purity practices, and so forth.

Relevant to the first century Jesus movement, while these volumes are not completed in their final forms until 500 CE, they include the debates beginning more-or-less concurrently with the composition of the gospel accounts (and apocalyptic Jewish literature, and apocryphal Jewish literature, and Qumran community biblical interpretation, and so on).

In short, and likely too generalized, Christian boundary markers include belief in the doctrines defined by the Church Fathers, and, these days, as articulated by (non)denominational statements of faith, while Jewish markers are ethno-religious identity and keeping laws and in-home rituals, fasting on Yom Kippur, or lighting Shabbat candles on Friday night—even knowing your deli order and how to navigate Katz’s on a busy Friday lunch “count” as Jewish. I hope that made you smile, but It’s very true. The cultural experience of Judaism is Judaism. Certainly, I am not an “observant Jew” (we note our matrilineal descent on mom’s side, I wasn’t raised Jewish, and my dad is a Protestant pastor, after all), and yet, we have an inside joke in our family about a non-Jewish friend who went to the deli and asked for a ham and cheese. This isn’t just a joke about kosher eating, which I do not follow, by the way, but this story actually evokes in me a visceral response! No kidding! While this entire story is tongue-in-cheek, the deli is an example of how Judaism shapes how a Jew lives their life, and “frum” or atheist, these labels and expressions of Judaism don’t matter for who counts as a Jew, and likewise, we all know our way around a pastrami on rye.1

Of course, not only to promote cultural awareness, but this is lived experience is important to draw out because being Jewish includes ritual and cultural touchpoints, and I’d argue, more so than in Christian settings. Don’t believe me? Just go to Instagram and search the hashtag #JewishFood and see how significant the cultural relationship with our food is to Jews. By the way, remember the Feeding of the 5,000 from last week?!

To return to the passage at hand in today’s post, while viewing the puzzle, composed in its final form, is meaningful and worthwhile, when we neglect its component pieces and the process of assembly, we’re missing a full characterization of “doing a puzzle.”

That Jesus (purportedly) walks on water is no less meaningful than examining its construction; indeed, noting its construction may offer yet more value than the final image.

The Hebrew Tradition of Power Over the Sea

A tratate in the Talmud Bavli relays this story, from Bava Batra 73a:

The Gemara cites several incidents that involve ships and the conversation of seafarers. Rabba said: Seafarers related to me that when this wave that sinks a ship appears with a ray of white fire at its head, we strike it with clubs that are inscribed with the names of God: I am that I am, YHVH, the Lord of Hosts, amen amen, Selah. And the wave then abates.

This tradition of the God of Israel’s name connects us to two places, well, to one place, the Exodus, and by extension, Moses, as told in two places: Exodus and Deuteronomy. In Exodus 3.14, Moses meets the God of Israel who identifies themself as YHVH, who calls Moses to lead the Israelites out of enslavement in Egypt. On the way, in the wilderness journey, Moses appeals to God who feeds the Israelites manna. Again, recall last week’s Sunday Post! But it’s not the feeding we’ll talk about now.

We see a compositional association with the Exodus and Mark’s and Matthew’s telling of the walking-on-water scene. In the Markan account, each feeding miracle is paired with a water miracle (JANT). The cycling of feeding-water brings to mind for the first century audience the liberation from enslavement (parting the red sea?), entering the land (crossing the Jordan), and, for Jesus’ audience, baptism! John the Baptizer performed his ritual immersion in the Jordan. The liberation is led by Moses, in partnership with the God of Israel, who proclaims himself to Moses. The concluding verse in today’s reading includes, “And those in the boat worshiped him, saying, “Truly you are the Son of God.”

Let’s follow this Son of God motif.

Jesus comforts the disciples, quiets their fear, joins them in the boat to calm the wind. Consider Deuteronomy 31:6:

Be strong and bold; have no fear or dread of them [enemies], because it is the Lord your God who goes with you; he will not fail you or forsake you.”

Here, in Moses’ farewell speech, he is handing off leadership to Joshua, who will guide them into the land. Moses tells the people of Israel to not be afraid, that he is with them, and places his confidence in Joshua, his follower and predecessor. We see the themes emphasized that we’ve discussed here. Again, what does Joshua do? He leads the people of Israel across the Jordan, into the land. Who is Joshua, the predecessor to Moses.

We pause to remember that Matthew’s author goes to great lengths to tie Jesus to Moses, including a flight to Egypt in the birth narrative and evading Herod’s edict to kill all the first born males, reminiscent of Pharaoh’s decree that sets up the Exodus narrative.

Conclusion: The Parts and the Sum of the Parts

Jesus’ walking on water, with control of the seas, like YHVH, or Moses leading the people of Israel out of enslavement, toward the land, over the Jordan; addressing the fears of the disciples, like Moses, commissioned by YHVH, in his farewell speech; when Jesus joins them in the boat and urges them not to be afraid or have disbelief, like Moses empowering Joshua to continue the journey. In the end, this scene of Jesus walking on water is thoroughly Christian in the cultural zeitgeist. I’ve never heard anyone say, “Can you walk on water like Moses?” And yet, exploring these scriptural references does not undermine Jesus’ authority for Christians when we expose the Hebrew basis for the proclamation; rather, it offers Christians the opportunity to connect their tradition beyond the first century of the common era, back to as early as the 12th century before the common era.

Jesus is the figurehead for Christianity, but for the gospel writers, Moses was the figurehead for Jesus. Viewing the construction of the text through its component pieces offers a portrait of the gospels that is more beautiful than its final composition.

Epilogue

In my research for today’s post, I uncovered a lot of apocryphal literature and secondary academic literature that informs our interpretation of today’s assigned reading. It’s too much to place that here, but I would love to publish a part two that connects this story to several apocalyptic works. Would you like to see that? Let me know in the comments!

Frum, from the yiddish, frumkeit, a religiously devout Jewish person. See: https://jel.jewish-languages.org/words/2206

Leave a comment